Category: Uncategorized

NEVER FORGET THE PNG COAST WATCHER HEROES

“Guadalcanal saved the Pacific, and the Coast Watchers saved Guadalcanal” – American Admiral William ‘Bull’ Halsey

Australians rightly are proud of the famous Coast Watchers for changing the course of the Pacific War in WW2 – but too few know that some of the bravest of that illustrious group were Papuan New Guineans.

On ANZAC Day, let’s not forget Paramount Luluai Golpak MBE , Sir Simogun Pita MBE and their fellow PNG heroes.

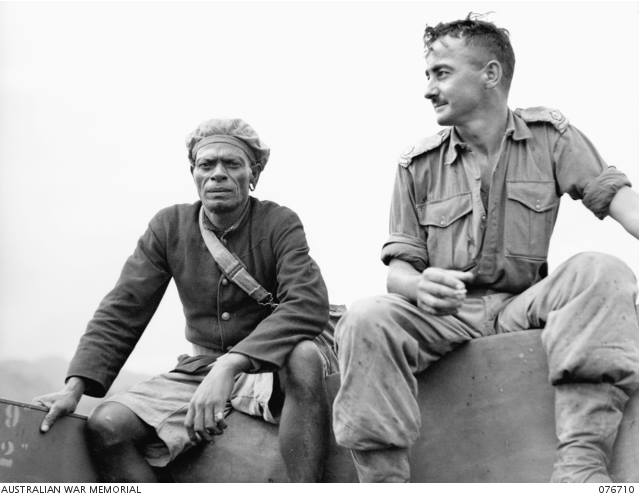

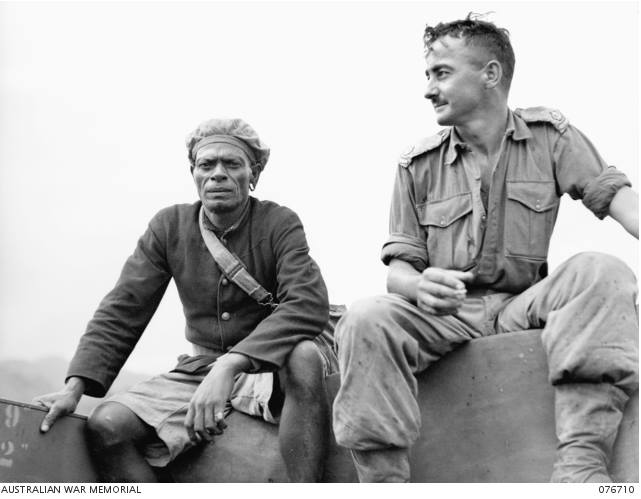

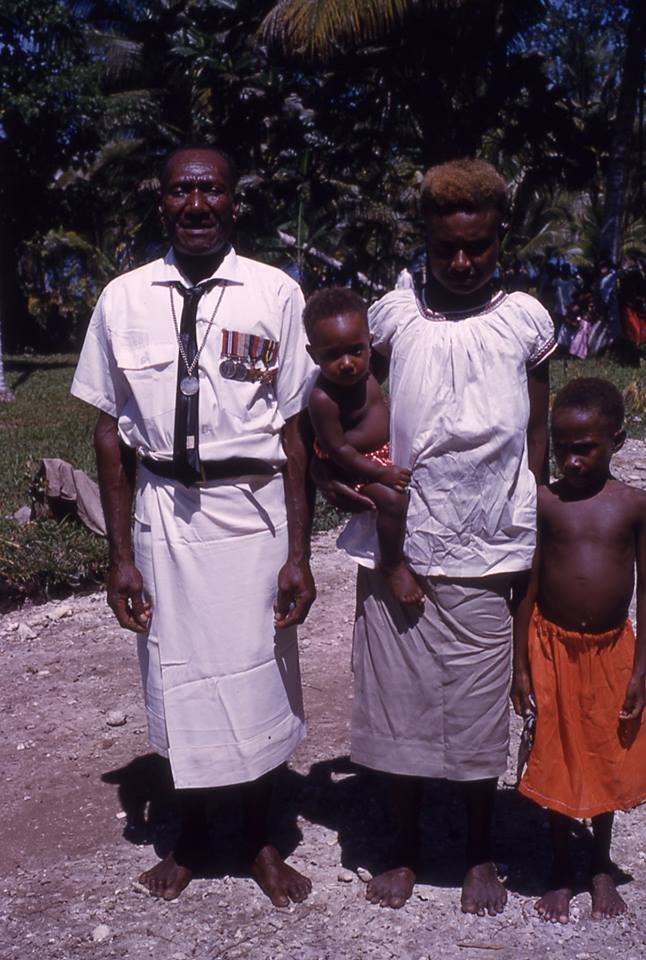

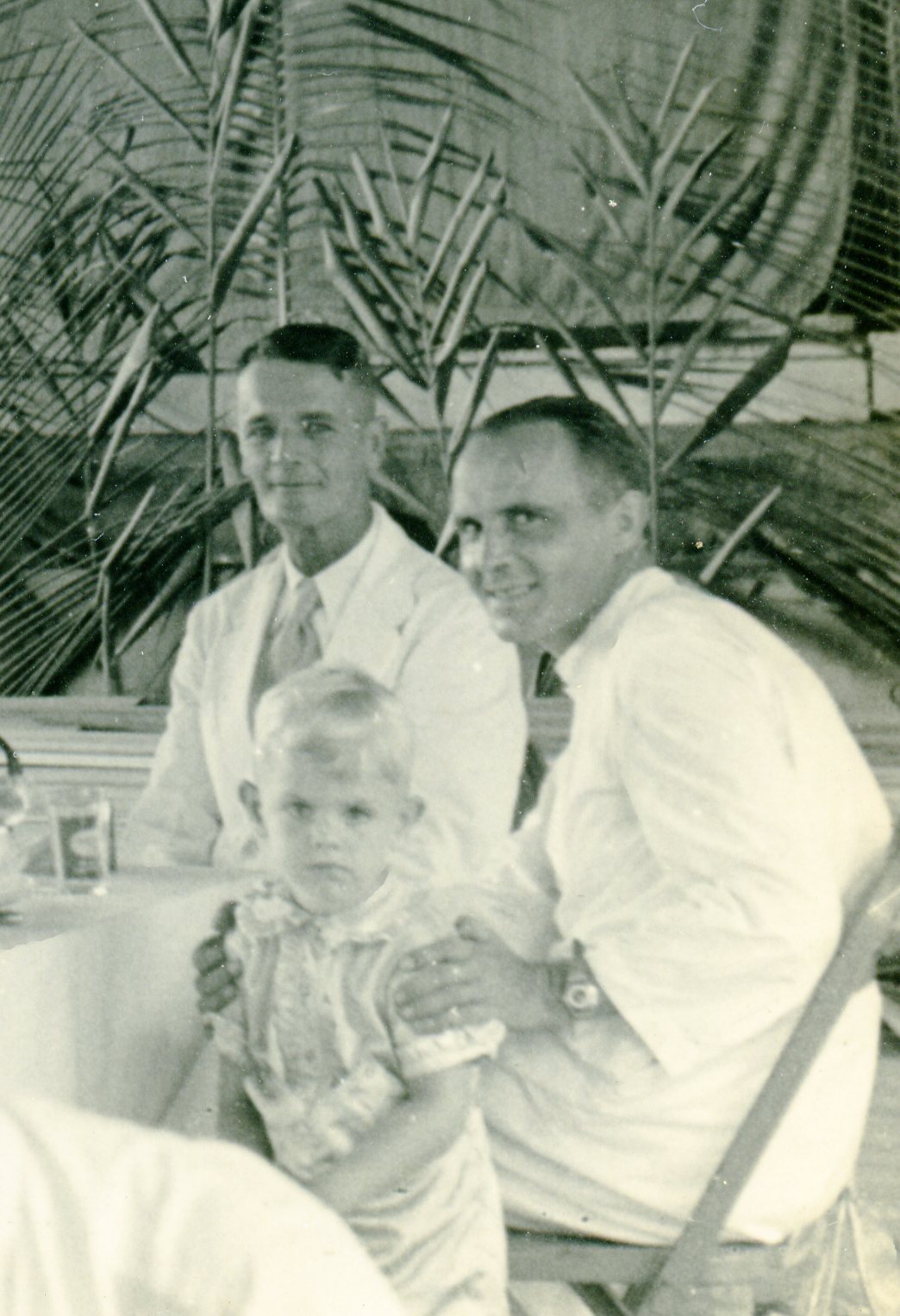

Golpak with Major AG Lowndes at Jacqunot Bay

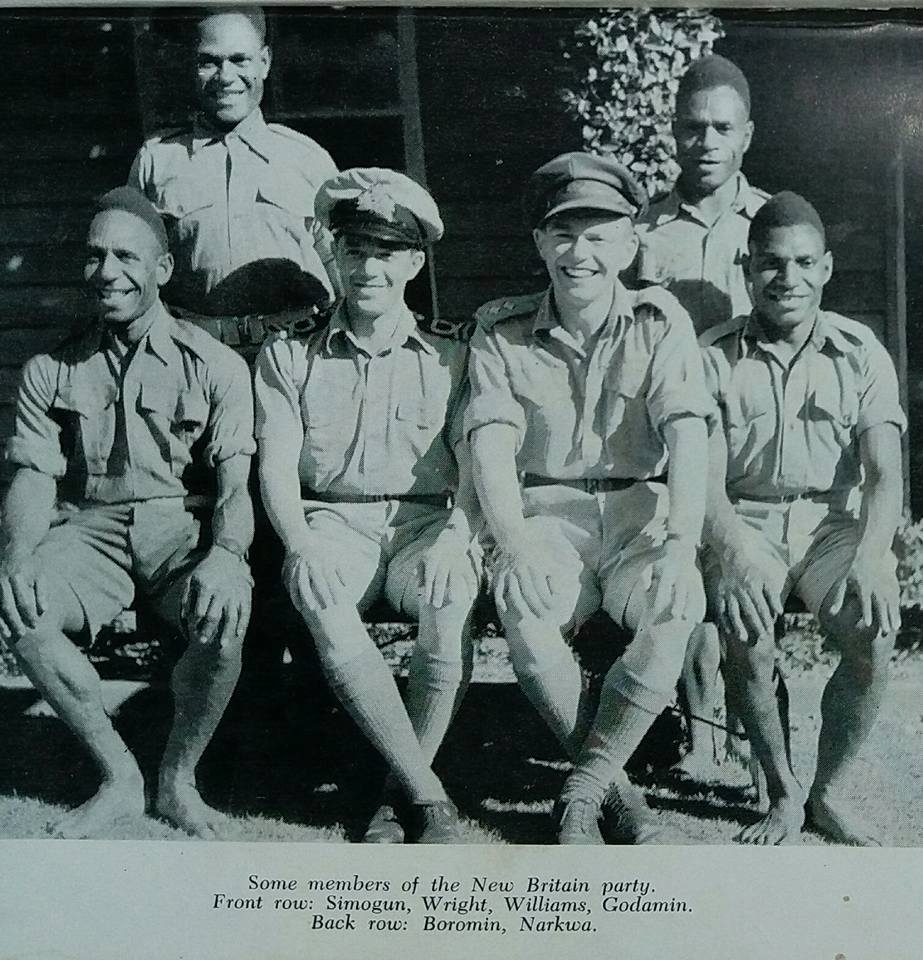

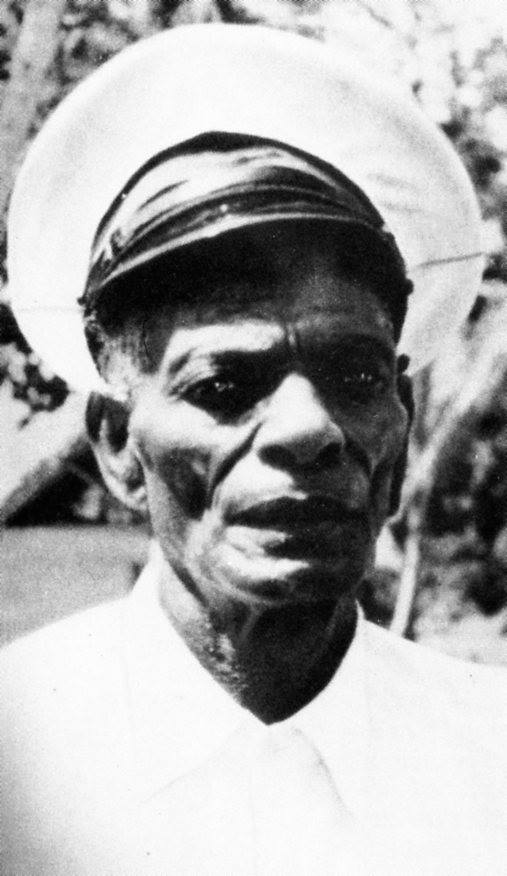

Simogun Pita

Australians and Americans owe them a massive debt. Many owed them their lives. We all owe it to them to never forget.

Golpak and Simogun risked their lives – and that of their families – operating behind Japanese lines, fighting the enemy and gathering critical intelligence for the Allies. Between them they’d saved Diggers escaping the Fall of Rabaul and numerous downed US and Australian airmen.

They’d been recruited by legendary coast watchers Malcolm Wright, Peter Figgis and Les Williams.

Golpak was from Sali Village in Pomio (New Britain) where there’s a school named after him. In 1961 one of the pilots Golpak rescued, Wing Commander Bill Townsend, was on hand as a special memorial was unveiled in Sali. Townsend is pictured below with Golpak’s son Kaolea .

I am indebted to former Pomio Kiap George Oakes for these marvellous colour photos of that event.

Photo by George Oakes

Paiaman, why helped Golpak in the war, and his family.

Author Peter Stone (Hostages to Freedom, the Fall of Rabaul) wrote about Golpak:

“Golpak showed tremendous loyalty, initiative and ingenuity in resisting the Japanese, and in assisting downed airmen and Allied Intelligence Bureau units in East New Britain.”

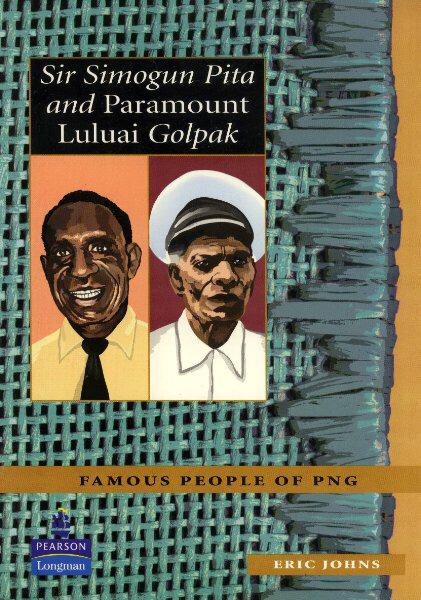

The incredible bravery of men like Golpak and Simogun is highlighted in various other books including Patrick Lindsay’s excellent The Coast Watchers, Malcolm Wright’s If I dieand this special tome on the two men by Eric Johns.

Forged under fire, the bond between the Papua New Guineans and Australians was unshakeable and the latter group ensured the courage and service of their brothers-in-arms was not forgotten higher up in the army and establishment. Both men were honoured as Members of the British Empire.

Simogun was born at Bargedem in East Sepik and had connections to Salamaua. He’d joined the mandated Territory of New Guinea police force and was a sergeant at Nakania in New Britain at the outbreak of the war.

In December 1942 in Australia Simogun joined a coast watching patrol destined for West New Britain and led by the naval officer Malcolm Wright. After preparations near Brisbane, on 30 April 1943 the patrol was landed from the submarine USS Greenling at Baien village, near Cape Orford. An observation post was established, from which Japanese aircraft and shipping movements were reported. In October 1943 the party crossed the rugged interior of New Britain to Nakanai, where they operated as a guerrilla force. Simogun led local men in attacks on Japanese troops. About 260 were killed for the loss of only two men. The party was withdrawn in April 1944. Simogun is credited with having maintained the morale of the group under often very difficult circumstances. Warned that the operation would be dangerous, he had replied: ‘If I die, I die. I have a son to carry my name’. He was awarded the BEM for his war service. Later he entered politics.

Simogun was the only Papua New Guinean to serve on all four Legislative Councils, from 1951 to 1963. Elected to the first House of Assembly (1964-68) for the Wewak-Aitape electorate, he was an active and influential member and under-secretary for police. Dame Rachel Cleland observed that he was a natural orator, whom no one could equal in style.

Appointed MBE in 1971, Simogun was knighted, recommended by the government of Papua New Guinea in 1985. He had married three women: Wurmagien from Alamasek village, Wiagua (Maria) from Boiken, and Barai (Bertha) from Kubren village at Dagua. Wurmagien had two children, Wiagua one, and Barai eight. Sir Pita Simogun returned to Urip in the 1980s and died on 11 April 1987 at Wewak. He was buried with full military honours at Moem Barracks army cemetery.

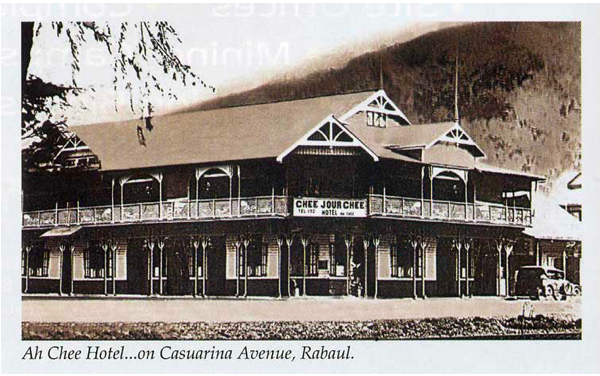

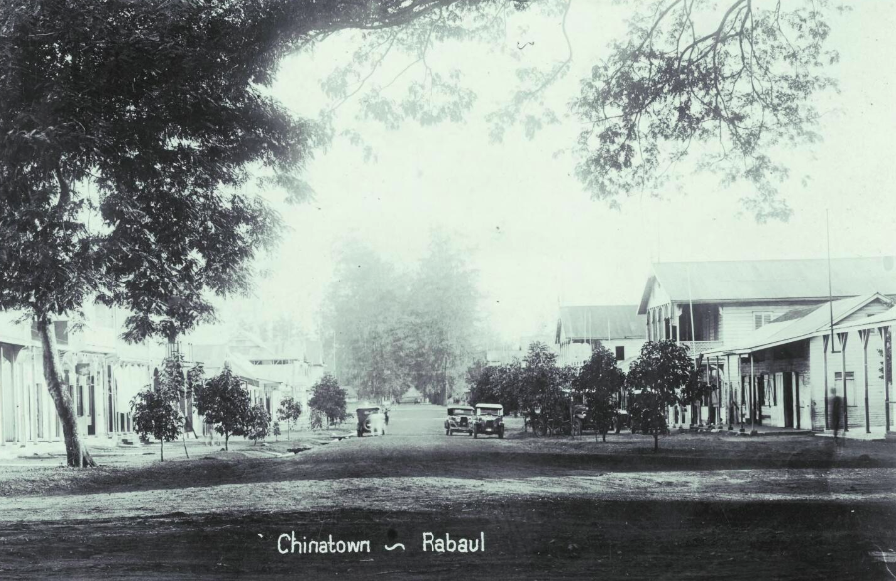

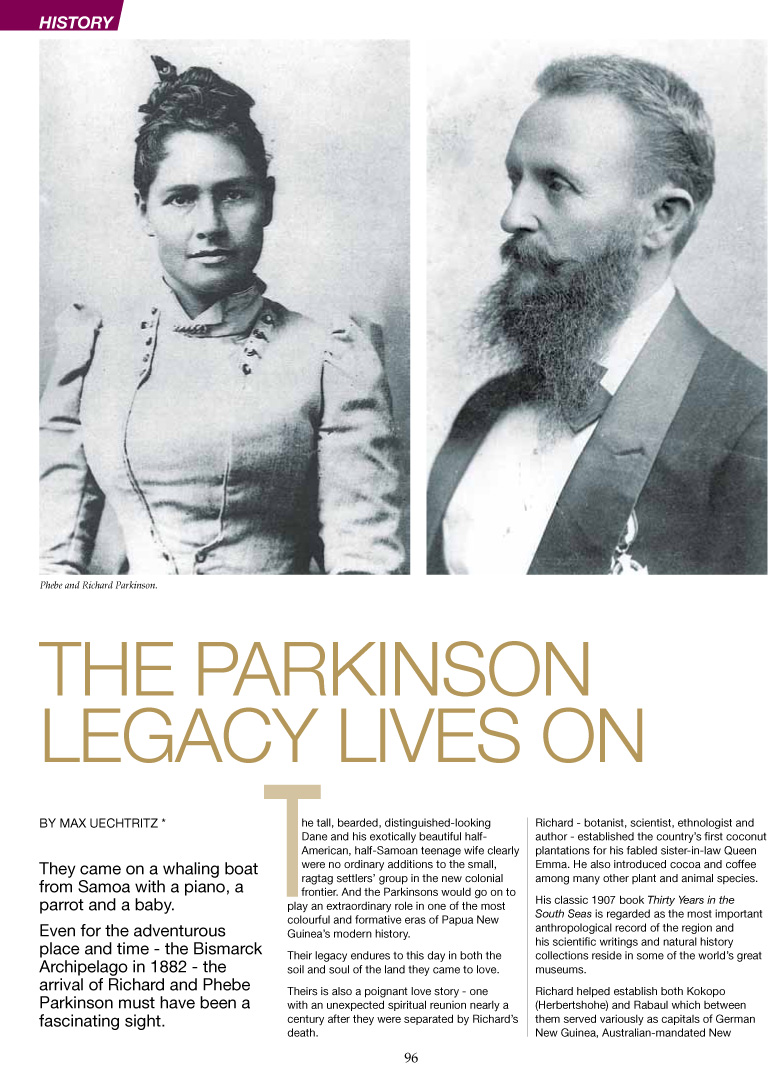

Ah Chee: Gentleman hotelier and Gem of the Pacific

If Rabaul in its halcyon days was the pearl of the Pacific town, then the human gem of the Pacific was its famous hotelier Ah Chee.

A small man with a large heart, Ah Chee’s innate kindness, generosity to those in distress and quiet dignity made him deeply admired, respected and befriended across racial lines in a time when that was sadly uncommon.

On his death in 1933, The Pacific Islands Monthly published an extraordinarily moving tribute – titled A Chinese Gentleman – saying he would ‘be mourned around the world’ and on reading it (see below) you can understand why.

It’s the stuff of potential documentaries and feature films about one of the most colourful destinations in one of the most fascinating eras of Pacific history. Ah Chee (Chee Jour Chee) should be better known. He sits easily among the pantheon of early settler characters in New Guinea including Emma Forsayth, Richard and Phebe Parkinson, Ah Tam, Governor Albert Hahl, George Brown, Rudolph Wahlen, Jean Baptiste Mouton, Bishop Coupé and Peter ‘the island king’ Hansen.

But like Ah Tam (himself an inspiring story for another time), Ah Chee had a tougher path to success than the others, simply because the overt racism of the time against Chinese who’d been brought to the islands as ‘coolies’. Rather than harden his heart, this discrimination had the reverse effect on Ah Chee, who opened his doors and, by default through his generosity, his wallet … to all and sundry.

*Ah Chee was decorated by Germany for his kindness to Germans awaiting deportation during WW1 and honoured by Chiang Kai-shek for his many donations to Chinese causes. Many down and out Australians benefited from the generosity of the man who started life in Rabaul as a cook. He’d served as a boy steward with the British Fleet before being brought to Rabaul in 1912 under indenture to the NGK.*from author Peter Cahill Needed but not Wanted, Chinese in Rabaul 1884-1960

Ah Chee’s Hotel eventually became the Cosmopolitan Hotel and the establishment under both names spawned generations of experiences and legends. Errol Flynn was but one of the colourful guests.

Here is the PIM article, which appeared in ‘North of Twenty-Eight’ column, probably authored by RW Robson who later wrote the Queen Emma book.

A Chinese Gentleman

“The last papers from Rabaul tell of the death of Ah Chee, who will be mourned round the world. Old Germans, of the Hasag- Hernsheim era, grieving in Hamburg for their lost estates in the Mandate, will pause sadly to remember him, and hundreds of Australians who knew him will join them.

“‘Ah Chee kept the hotel opposite Ching Hings in Rabaul, on the corner of Chinatown. Other hostels came and went. The new post-war Mandate Administration formed three clubs and a “white” pub opened its doors, but “Ah Chees’ survived.

“There was a large bar on the ground floor and a dining-room in which an old German musical box with a peculiarly sweet voice played “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling” over and over again.

“The hotel of Ah Chee was built of wood and set on volcanic ground, so that every sound in it was amplified. The walls of its bedrooms, which opened through French lights on to a broad verandah, had been cut off a foot or so from the ceiling for ventilation. Each room was furnished with a specklessly clean bed with a sheet and a mosquito-net, a washstand and one chair.

“Bed is the coolest place in Rabaul, and to lie there in the evening a decade ago was a cosmopolian adventure, for nothing was hidden in Ah Chee’s. You could hear every sound in the bar—the “prosits” of the sad expropriated, the “Ludwig-two-bottle-beer-he come” of the Civil Service, the arigatate kamisen of the visiting Jap skipper, the lusty “Whisky soda along King George— quick-time” of the arrogant police in for their free “nine o’clock”; the whispered love tale on the verandah ; the domes tic discussion three doors down ; the sage debate between committeemen as to whether the salary of you, a stranger, would be £6OO a year, which would make you eligible for membership of the Rabaul Club. Somebody, perhaps, would be playing a concertina round the corner, not loudly enough to mute the malarial sobbing of the sick Teutonic planter just bereft of the results of his life work.

“Above all the medley song would rise.

“German voices in the dining-room lifted the roof with “Ein Pflanzer auf ein Kiistenreis ” The musical box did its best; the picture-show gramophone across the road blared “Susie”; the stewards off the Norwegian boat shouted “Ja, jeg elsker dette landet” without blotting out the insistent “You did,” “I didn’t” of two Cantonese engaged in a long-drawn quarrel in the street against a background of native sing-sing wafted across the hot kunai grass in the moist square.

“Through all the babel and turmoil moved Ah Chee, never disturbed, always gentle, kind and smiling. When the young Australian girl next door fell ill of fever and the oppression of the tropic atmosphere, the little man was there in person with cool drinks and comfort.

“When the drunken sailors on the steps at 3 a.m. were moved to wrath because you threw water on them as they sat singing “Ma,” it was Ah Chee who arrived, placatory, pleasant, unruffled, and, looking smaller than ever in a pair of loose pyjamas, persuaded the outraged mariners not to knife you and burn the house down.

“Fights in the bar, attempted suicides, gurias which seemed likely to shake Rabaul into the sea, oppressive ordinances, cheeky locals —none of them rattled Ah Chee.

“And the poor were always with him. The German deprived of his property by the fortune of war, the shell-shocked youngster ruined by high living, the gambling fool with the empty pocket, the weakling taken in crime and in search of bail, the hungry and the thirsty, deserving and undeserving—all patronised him. Paper and pencils were cheap. One more chit would be added to the pile in his little office with a gentle “Some time you will pay me.” But nobody ever did.

“Ah Chee was a legend through the Pacific. He even got into the songs of the colorful Bismarcks in the days when “Willst du reich werden” was still sung:

Will you be wealthy? Down to Rabaul flit, Stay at Ah Chee’s for months and pay by chit;

Fill up your sleeves with ace and king and joker,Then start indulging in a little poker.

Produce those jokers from your sleeve—be stealthy, And then if you aren’t caught you’ll soon be wealthy.

“A fortnight after Ah Chee died, his flowerlike wife and his fine young son did something on Christmas Eve which must have pleased the spirit of the little hotelkeeper. They gave a banquet in his memory. Eighty people came to it. Men of the old German time, civil servants, white traders, Orientals joined in a party which only needed the Absent Guest of Honor to make it a representative human historical gallery of all Rabaul’s past.

“But I’ll wager that a good many of the guests owed Ah Chee a lot more gratitude than is represented by sitting at a man’s dinner-table as the guest of his estate. ”

Ah Chee’s legacy continues to this day through his descendants in Papua New Guinea.

His son Chin Hoi Meen became a pillar of society, famous photographer and war hero who helped rebuild his beloved Rabaul after its destruction in World War Two.

*The hotelier’s son was given official recognition for his wartime bravery in 1949 when he was awarded the King’s Medal for courage and service in the cause of freedom. This medal is intended to acknowledge those who perform “acts of courage entailing risk of life or for service entailing dangerous work in hazardous circumstances in furtherance of the Allied cause during the war.”

In 1954, Chin Hoi Meen was presented to the Queen as a war hero in Australia for his services to the Allied Forces and for risking his life to rescue two American pilots who were shot down. * courtesy Noel Pascoe

Ah Chee should be remembered as a Legend of Rabaul.

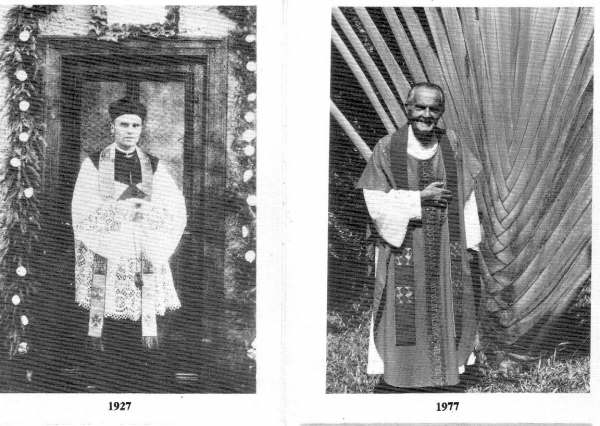

Shakespearean tragedy in Rabaul: the Earl of Chichester’s secret son and the famous priest who dared.

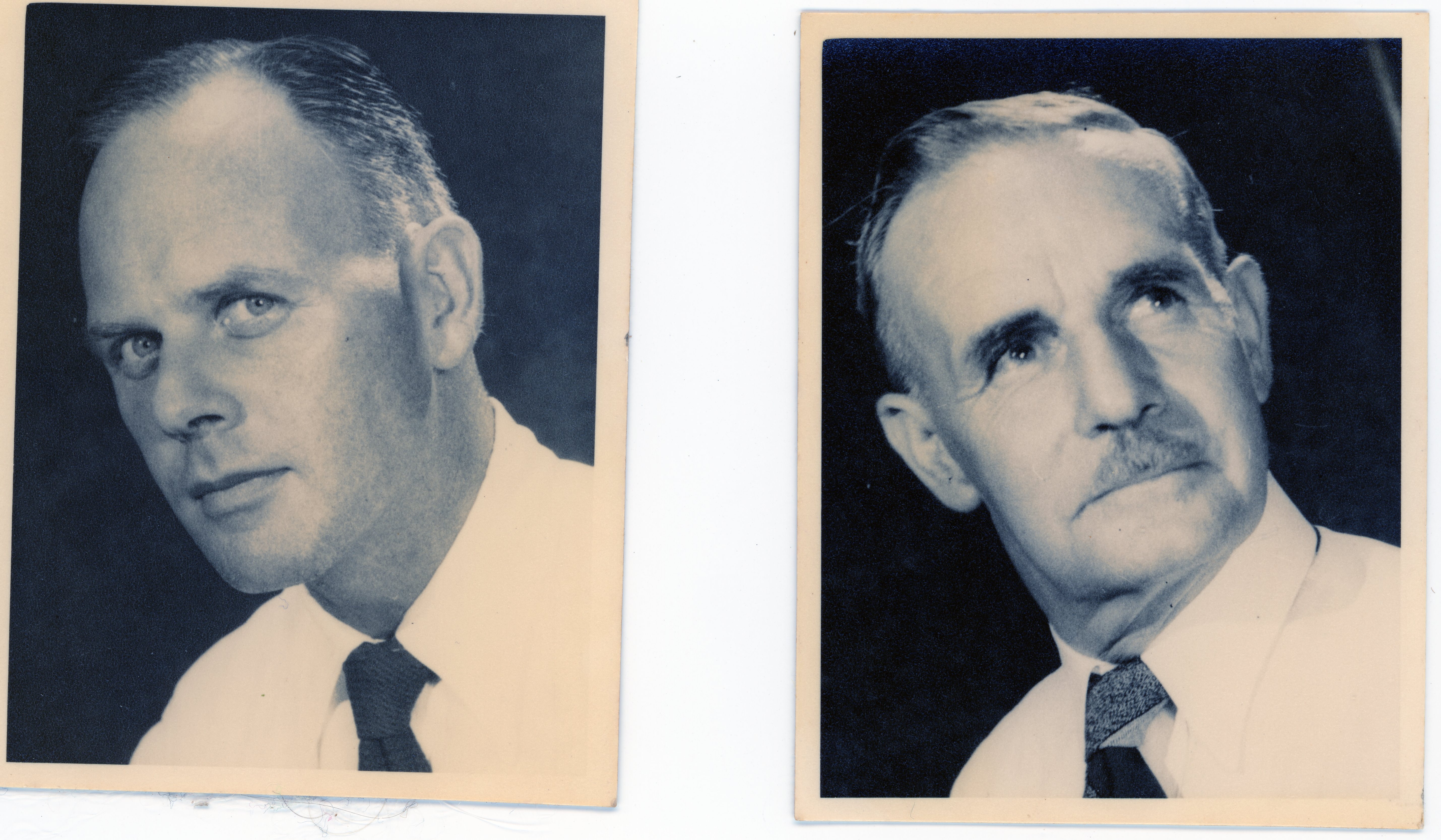

Few knew the secret of popular former Rabaul character Arthur Savage: he was the son of English nobleman, the Earl of Chichester.

Fewer people still knew that one of Rabaul’s most beloved identities – Father Bernard Franke – ignored strict Catholic rules to give Arthur a proper funeral and burial after he committed suicide thinking he had cancer.

He didn’t have cancer. But tragically his “all clear” medical advice arrived a week after his burial.

The revelation about Arthur Savage being of noble blood and his tragic end came from my mother Mary Louise Uechtritz before she passed away last year.

Arthur was a close family friend. He’d had walked Mum down the aisle and given her away at her wedding to Dad (Alf) at Rabaul’s Francis Xavier church on April 26, 1952. He was godfather to their first child, my eldest brother Peter. In a favourite family photo, a grinning Arthur is pictured with Mary Lou and Alf at the Frangipani fancy dress ball. Typically, the passionate art lover and thespian dressed as a French artist at Montmartre .

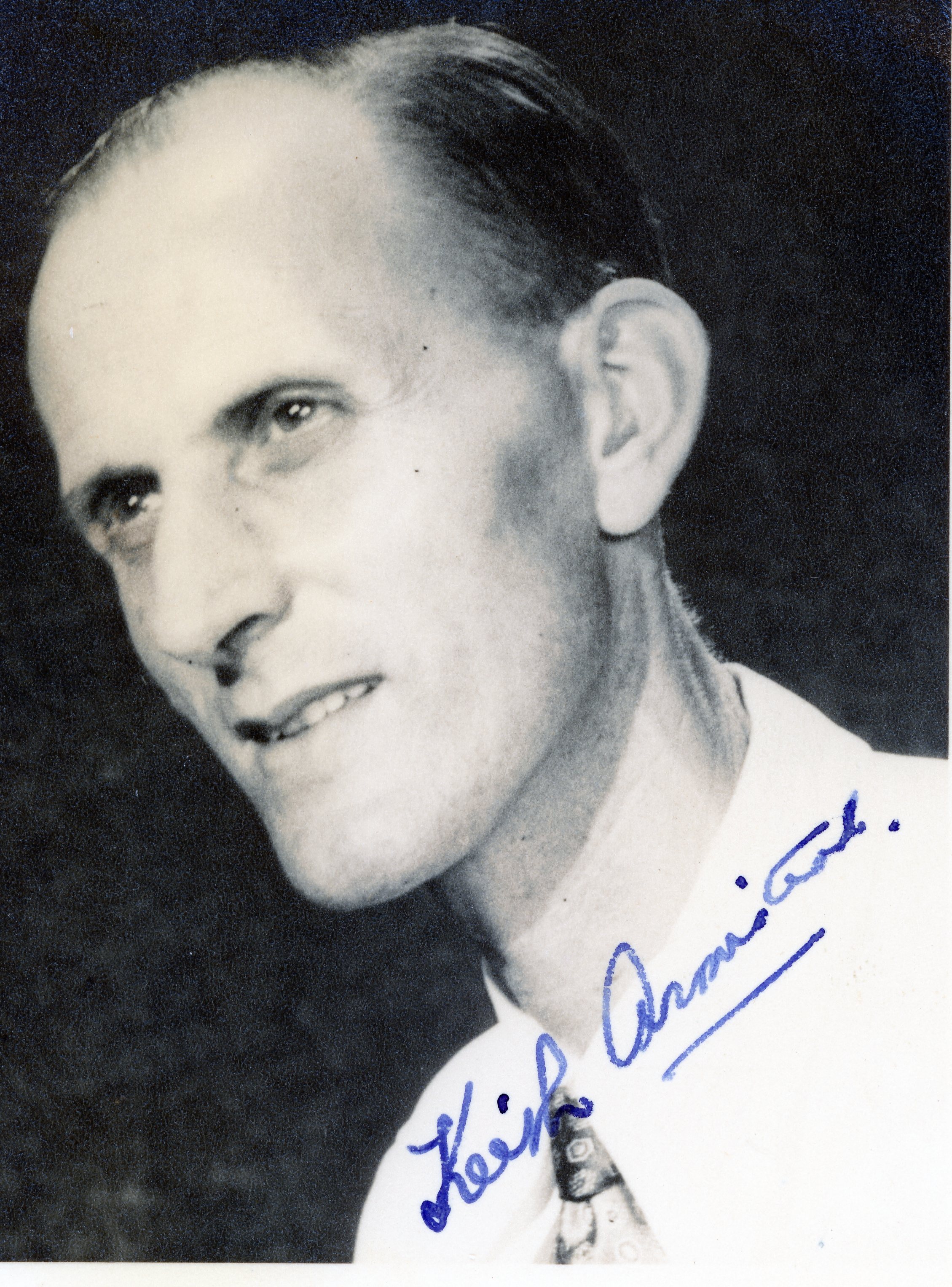

Arthur also wrote plays and performed in them for the Rabaul Dramatic Society. The production pictured in the title photo above was ‘Ghost Train’ and features Arthur (far right), my mother , Keith Armistead in the group.

“He was extremely well educated and had a real love of literature and the fine arts,” Mum told me. “Arthur was the ‘illegitimate’ son of the Earl of Chichester, who was very fond of him and insisted he had the very best education.”

Arthur Savage (right)

Arthur walked mum down the aisle in the post-war Francis Xavier catholic church, Rabaul

Arthur went to Beaumont College and then the famous Ampleforth College in Yorkshire (left)

It’s not certain how he ended up in New Guinea but he eventually ran the plantation Asalingi on the north coast for my Dad’s stepmother Rita (Uechtritz then Roberts ) and her second husband Tex Roberts.

Mum recounted with great merriment – for a lady herself raised by nuns in a French convent in Wales – how Arthur and his great friend Ned Shields were particularly fond of a drink and stayed up all night imbibing and carrying on.

“He and Ned would be up at dawn, whiskies in hand, wandering down the beach and into the sea fully clothed quoting Shakespeare,” she said.

Then came tragedy. Arthur contracted cancer of the oesophagus. I am not sure whether it was a false diagnosis, or he had an operation to remove the cancer. Anyway, Mum said Arthur couldn’t bear the thought of dying a slow, horrible death with chemotherapy and took his own life. His ‘all clear’ message from Sydney sadly arrived in Rabaul a week later.

Father Franke was in every sense the ‘people’s priest’. He ignored the Catholic ruling that those who had committed suicide were unable to be buried on sacred ground or receive a funeral Mass. He performed what can only be presumed was a clandestine funeral and Arthur was buried in Rabaul cemetery.

Arthurs father was the Sixth Earl of Chichester, Jocelyn Brudenell Pelham (correct spelling) who died in 1926. He was awarded an OBE in 1918. It is unknown whether Arthur maintained correspondence with him during his New Guinea years. Given Mum’s account of him, somehow I think he did.

Arthur Savage’s father, the The 6th Earl of Chichester

Rabaul Dramatic Society: Cathy

Rabaul Dramatic Society: Mrs Sutherland

Rabaul Dramatic Society: Ron Judd

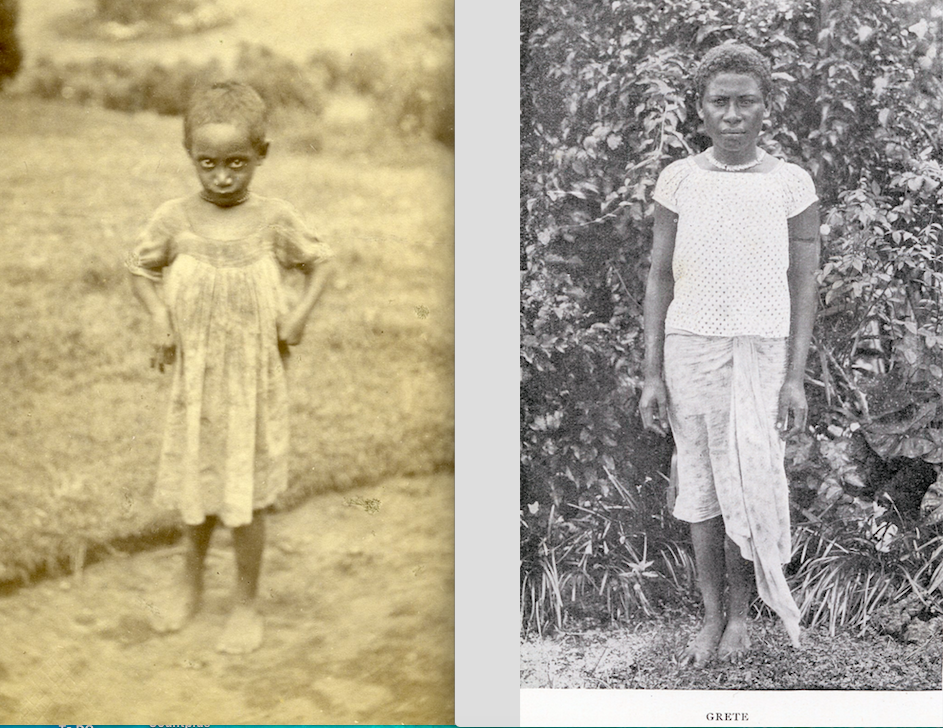

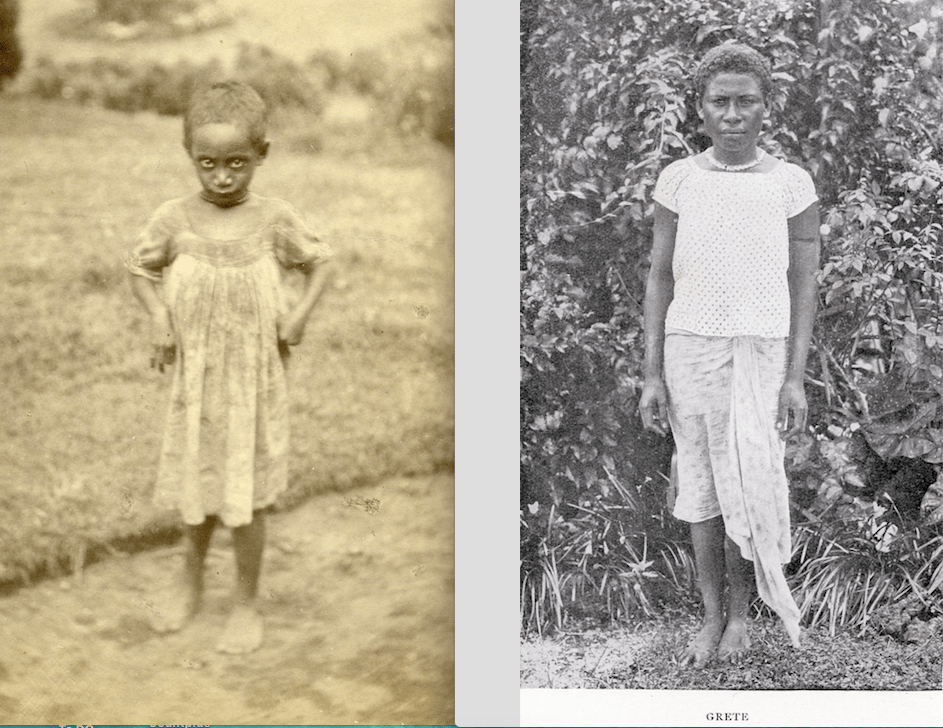

Phebe Parkinson and the little orphan girl Grete

There seemed no hope of life or love for little orphan Grete.

The newborn would be an indirect victim of the blood-soaked struggles – murders and punitive slaughters – between islanders and colonials in the Bismarck Archipelago early last century.

But she was saved by the compassion of my great grandmother Phebe Parkinson, who took her into her home at Kuradui plantation near Kokopo on New Britain and nursed Grete back to health.

Grete would grow up to become “Head Meri” – the senior female staff member – at the home of Phebe and her distinguished husband, the Danish anthropologist Richard Parkinson.

She would have overseen the staff serving the banquet at the grand farewell given at Kuradui for Queen Emma, Phebe’s sister, in 1911 then Australian military officers in Kuradui garden parties after they seized New Guinea from the German administration in 1914.

Now, my family – Parkinson descendants – are searching for descendants of Grete.

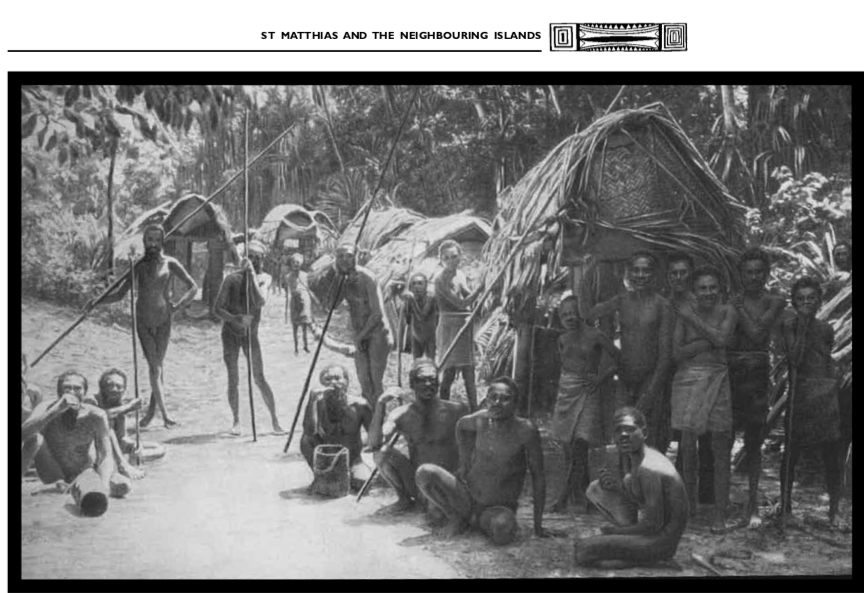

This story all started in 1901 on tiny island in what’s now the New Ireland Province. It’s part of a small archipelago group then called St Matthias Islands or Mussau islands.

A well-heeled German traveller anchored his large luxury vessel Eberhard at Mussau in what was supposed to be a scientific exploration called the First German South Seas Expedition. My grandfather Richard Parkinson was no fan and wrote in his famous tome Thirty Years in the South Seas wrote, “it became clear that science lay not so close to the heart of the owner of the ship as pleasure”.

The locals had been in continuous war with foreigners since 1864. Their only other contact with outsiders was when William Dampier ‘discovered’ the island on St Matthias Day, February 24 in 1700.

At first the locals seemed to accept the visitors. Then the Eberhardwas sent back to the mainland to fetch forgotten supplies. The camp was exposed and attacked and the Germans were speared. Herr Mencke and his secretary Herr Caro were fatally wounded while others escaped. Later, some traders of the Hernsheim Company were also killed. These attacks led the Imperial Governor von Benningsen to order a punitive, revenge raid by the German warship Kormorann.

Parkinson wrote: “A not insignificant number of St Matthias people were killed and several women and children as well as a teenage youth were taken to Herbertshöhe (Kokopo) as prisoners.”

Lilian Overell in her book A Woman’s Impression of German New Guineatakes up the story:

Among them was a woman, who, before dying of fever and fright, gave birth to a baby girl.

The Governor sent for Mrs Parkinson and begged her to take the starving little baby. “I am afraid it will die,” she said.

“It only has one chance in life ,” replied the Governor, “and that is in your care.”

So Miti (as Phebe was referred to by locals in their word for Mother) took the wailing mite of humanity home and showed it to her husband.

“It is not going to sleep in our bedroom,” he said, looking at it with aversion.

“Very well,” said Miti cheerfully, “I’ll sleep with it in the rice house.”

Of course he gave way.

Overell wrote: Phebe (Miti) fed the baby by tying rag over the neck of a bottle of milk, and for three months it sleep in her motherly arms. It began to thrive and grew into a strong, healthy child. Grete was very jealous of anyone whom her mistress showed affection.

It is notable that Phebe had 10 children of her own and she had also taken in other ‘war babies’ who were destined for a life of slavery to those who’d killed their parents and seized the children in tribal conflicts.

The photos at the top of this article are both of Grete. The first one as a little girl is from the collection of Nellie Diercke, the eldest Parkinson sibling and older sister to my grandmother Dolly Parkinson. The second image on the right is from Overell’s book and shows Grete as a young woman.

Kuradui is still a sacred place for the Parkinson descended Uechtritz and Diercke families.

In 2004 Phebe’s remains were buried there next to her husband in the family matmat or cemetery. My brother Gordon had found Phebe’s grave on New Ireland 60 years after she died of starvation in a Japanese prison camp during WW2. In one of the great moments of his life, our father Alf Uechtritz oversaw the ceremony where Phebe was reunited with her husband Richard. That’s a whole other story.

Our family is returning to Kokopo and Kuradui in September to place the ashes of our beloved parents Alf and Mary Lou in the Parkinson cemetery. With us will be the Diercke family who will also lay to rest the ashes of my cousin Chris Diercke alongside his brother Michael, father Rudi and grandmother Nellie.

We are privileged that the owners and custodians of Kuradui lands will welcome and host us. It is a very special relationship.

Phebe Parkinson in particular was renowned for her huge heart and love for the islands and their people. She was half American and half Samoan. But when Queen Emma urged her to move to a life of luxury with her in Sydney, Phebe declined: “These are my people,” she said.

So, the story of the Parkinsons is not your typical colonial, pioneer story. It is inextricably linked with the people of New Britain, Kokopo, Rabaul, the communities of what were Ralum, Malapau (Parkinsons first plantation), Karavi, Raluana and Kuradui.

It is also the story of those like little Grete and that is why we are keen to find any of Grete’s descendants and nurture and grow that story.

For those reading this in East New Britain or who’re from the area , please do put the message out for any remaining members of Grete’s family. Unfortunately I do not know her family name. You can direct message me on facebook.

Our Wedding Day

April 26 (1952) was my big day! I was quite excited and very nervous when I woke up at the Cosmo hotel. My boi had ironed my shirt and pressed my sharkskin suit. After I had dressed, I ordered a taxi to come and get me to go to church.

Rudi Diercke (left) Chris Diercke (front)

Our friends were already gathering around the church plus some sticky beaks.

The only members of my family were Rudi and Gwen Diercke and their children. Mary Lou had only her mother. Though Father White was to say mass and marry us, I was met by Father Bernard Frankie.

He told me what we needed to do, where to kneel, etc. He was really beaming and kept telling me what a lucky guy I was to get Mary Lou Harris!

Bob (Sutherland) arrived with his mother and we were ushered into the church and told where to stand. I made sure that Bob had the ring! Soon Mary Lou arrived. She was given away by our friend, Arthur Savage. They came up the aisle and Mary Lou knelt beside me. She looked very beautiful. I just couldn’t believe that she was about to marry me!

Father White came into say Mass as attended by Father Franke.

So, OUR MASS started, and the time came for us to say all the things required to say to become man and wife.

I could see that Lou was also a little nervous. To be quite honest, I don’t think that I was able to follow the Mass as I should have, except when it came to receive the Sacrament. Then I really thanked God for giving me Mary Lou.

When Mass finished, we went to the Sacristy to sign the books. Then I had my wife on my arm and we walked down the aisle to the front of the church. There, the Girl Guides formed a Guard of Honour.

The bridesmaids were Wynne Ann Legge and Pat Ives. The flower girls were Alannah Parker and Sharon Whalley, and the page boys Christopher Diercke and Anthony Parker.

The main wedding group posed photos were taken at the door of the church.

We then walked across the yard to the Xavier Hall. Soon all the speeches were being made, and I had to make my speech, and was very nervous as I had never made a speech before. I felt a bit tongue tied but it wasn’t too bad. We had a wonderful reception. It was great to have all our friends around us.

From left: John Carroll, Alf, Fr White, Col Parry, Mary Lou, Alannah Parker, Usula Harris

Jack Thurston was very special as he had been a great friend of my father.

As mentioned earlier, he had made his boat Karlamanus available to take us to Sum Sum.

He was going to skipper it down himself, although he had his own captain.

When it was time to leave for the ship, we got into one of the new Chev cars to take us to the wharf via Lou’s home, where she had to change. Friends had tied tin etc. on the back of the car, so we made a big rattle leaving the reception whole.

Incidentally, that hall had been beautifully decorated by John Carroll and his Boy Scouts.

The Karlamanus was tied up at ‘wreck wharf’. Most guests also came down to see us off. After lots of farewells and “Good Lucks’ we left for our trip to Sum Sum.

We must have left about midday or soon after as it took five and half hours at least to get to Sum Sum.

The Karlamanus was a fast boat so we got to Sum Sum just before dark.

All the plantation workers and their waveband children were at the beach to welcome the new Missus. Our baggage and cargo was unloaded and we went ashore.

All the plantation workers and their waveband children were at the beach to welcome the new Missus. Our baggage and cargo was unloaded and we went ashore.

As we went into the new house I observed the tradition of carrying a new bride across the threshold. Our new home was just about finished.

I think one spare bedroom still had to be lined. We asked Jack to stay for a bite, but he wanted to get going. So we had a bottle of champagne and saw him off! We lit our kero lamps and had a bite to eat from the leftovers of the reception.

Most couples went off on their honeymoon to somewhere other than they home. We didn’t. We had a wonderful honeymoon on the plantation itself, exploring and swimming up the Sum Sum river. Swimming along the passages in the reef. Collecting shells and food on the reef. Fishing. Driving in the jeep.

That was the start of our life together.

Sum Sum Plantation house : our first home

I wonder if on that day we knew what was ahead of us in years to come, how we would have felt!?

I am writing this 45 years later and have 10 children and 25 grandchildren.(*note in 2019 now 32 grandchildren , 23 great grandchildren with three more on the way)

There have been trials and problems and unforeseen situations, as the rest of this story will confirm. But all in all, we have been greatly blessed and have had so much to be thankful for.

The Journey Begins

Thanks for joining me!

Good company in a journey makes the way seem shorter. — Izaak Walton