By Max Uechtritz

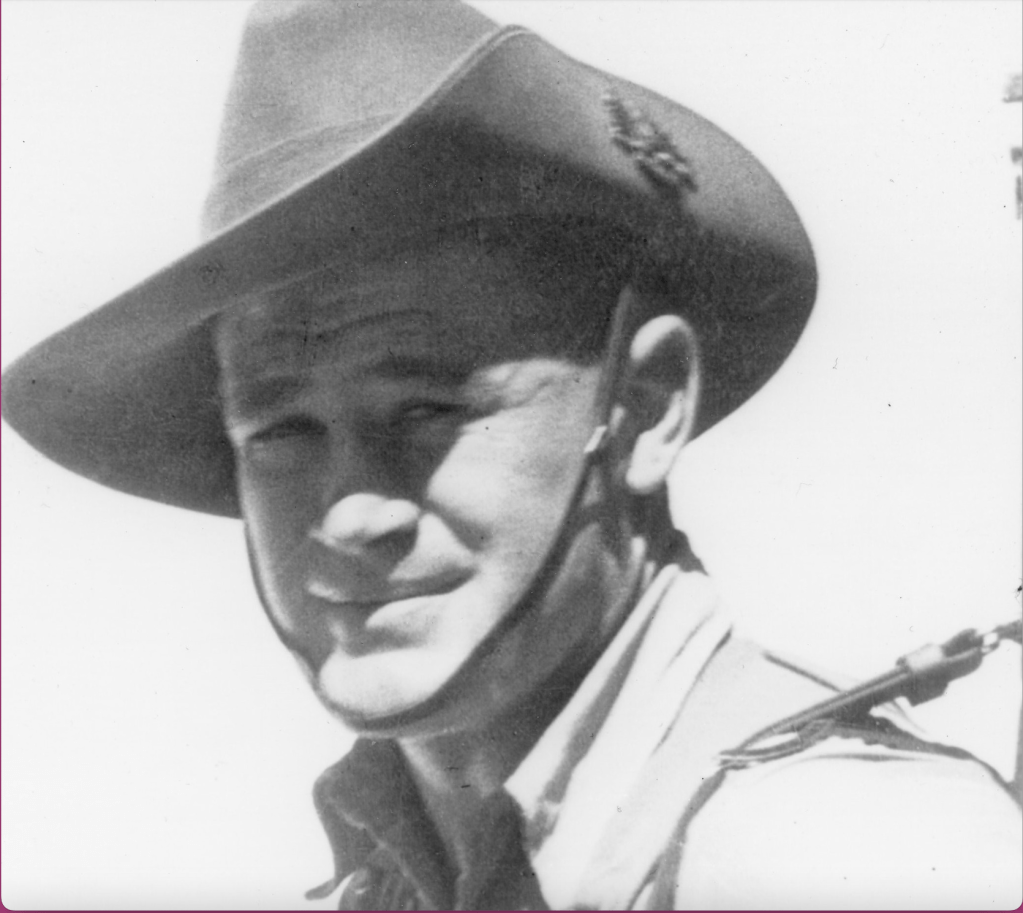

Little Ivor Gascoigne pleaded with his mum not to be evacuated with her on the last ship out of Rabaul before the Japanese invasion.

Ivor was 15 years old that late December day 1941, when hundreds of women and children from the New Guinea islands were scrambling aboard the islands passenger ship MV Macdhui. Pearl Harbour was attacked barely three weeks earlier. Everyone knew Rabaul, capital of the then Australian Territory of New Guinea, was in the sights of the Imperial Japanese Navy.

Ivor was flushed with his first job as a copy boy. Besides, he wanted to stay and help his Dad, Cyril. But the rule was that children under 16 must be evacuated. His mum finally reluctantly, tearfully, relented. Ivor was given special permission by authorities to stay.

The decision would haunt and crush her for life: her son and husband were captured in the expected invasion 28 days later, interned as POWs then perished together when the Japanese prison ship, MV Montevideo Maru was sunk off the Philippines on July 1, 1942.

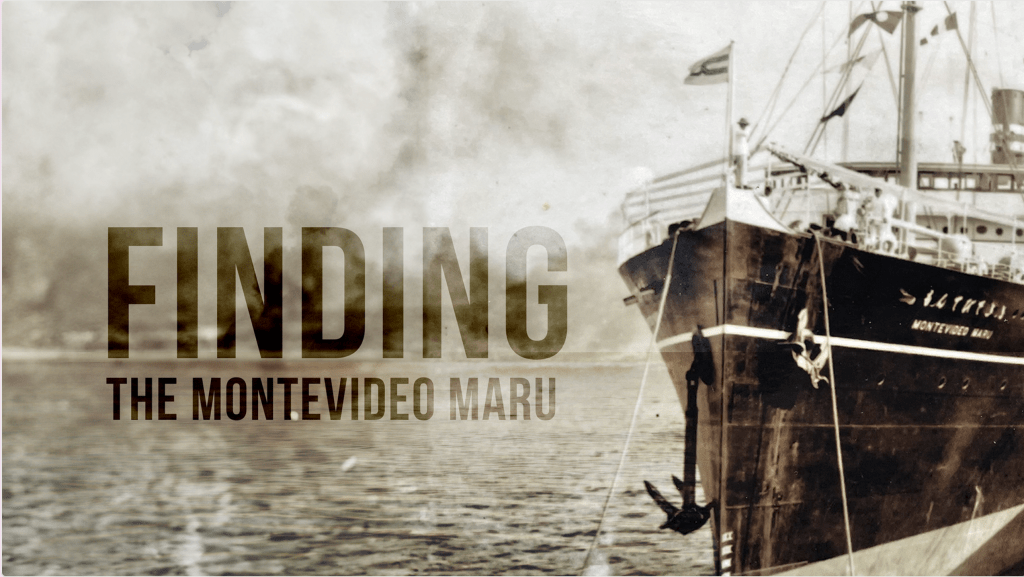

Nearly 1000 Australian men and boys perished along with Allies from 13 nations. It was Australia’s greatest maritime disaster. It was also our greatest maritime mystery – and most overlooked tragedy – until April this year when the Silentworld Foundation expedition team finally found the war grave wreck in 4200 metres deep waters off The Philippines. The whole episode has also been one of national shame – to anguished relatives who suffered generational trauma, denied closure for themselves, recognition for their loved ones and, for decades, even the dignity of commemoration in the national narrative.

That’s why tomorrow (Monday Nov 27) night’s special commemorative dinner for descendants, hosted by Silentworld at the Australian War Memorial with the Prime Minister in attendance will be a special milestone moment in a tragedy few Australians know, but all should.

More on that below, but first it is important to acknowledge the torment of the women who clung to hope for their men and boys and families torn asunder by bewildering loss, official silence, guilt and regret.

Grief resolution took years and in this particular case four decades:

One family decided that their lack of a funeral in 1942 was contributing to the way in which their grief was still unresolved 40 years later. In about 1982 at the suggestion of the therapist, the Spensley family enacted a funeral ceremony for husband and father. Funeral Directors and a hearse with a coffin bearing the nameplate of George William Spensley arrived at the psychiatrist’s rooms where a celebrant conducted a funeral in a setting of flowers and candles, and in the primal room, a big, padded room’ the relatives :

“went down into the grieving and having to say to each other what we really needed to say. It was a very intense affair. It was very important.”

That’s an extract from the incredible research author Margaret Reeson gathered for her Masters thesis and book A Very Long War, and so is this:

“Arthur Brawn, a Methodist minister, who had been a friend and colleague of the Methodist men who had died, conducted private commemoration services in New South Wales for many years. In churches, school halls, a retirement village and RSL clubs. Sometimes the only other person present was the caretaker.“

One of those Methodists was Sidney Colin Beazley, uncle of former Opposition leader Kim Beazley and Ambassador to the USA , now chair of the Australian War Memorial council.

For some of the wives and children who’d been evacuated to Australia there was not only immeasurable anguish at being kept in the dark, but there was also the cruellest of financial consequences. Because their husbands had not been formally declared dead, there was no war pension. No income. Some young mothers had no choice but to put their children into orphanages and go to work in factories to sustain themselves.

Some families, right up until late 1945, were sending Red Cross aid packages addressed to their men, supposedly alive as POWs in Japan. Then came the devastating telegrams that their loved ones had perished more than three years earlier.

(Reeson) At various times rumour had it that the Rabaul men were in Manchuria or seen on the street in the Philippines or loading cargo in Japan or on Watom Island off New Britain. But there was nothing of substance. Mrs Tyrell, an officer’s mother, wrote of the monthly meetings of the Rabaul Fortress Relatives Association, ‘It is quite pitiful to see so many who have never heard one word from their loved ones. I do hope and pray they will hear soon.’

…any means of hearing news became of prime importance to the anxious families, radio news reels, newspapers and the Postal Service all took on powerful roles in daily life. One woman described the stress of waiting for the post: ‘In those days, the postman came twice a day, and you just waited from one postman’s whistle to the next, and it just went on and on and on.’

(Reeson) Mrs. Lyons, mother of young soldier Vin, was deeply embittered towards ‘officialdom’, so much so that she rejected the medals awarded posthumously to her son by the government which had let him die.

“One dreadful day my brother’s metals arrived. I never saw them. She threw them out. My father described it to me. She took the lid off the dustbin and threw them in.”

When inquiring about the eligibility for a female relatives badge, worn with pride by women whose men were serving overseas, wives and mothers of Rabaul militiamen were informed that they were not eligible because members must have embarked for service with the AIF beyond the limits of the Commonwealth of Australia. Those serving in Darwin, Rabaul and the mandated territory are not considered to be serving abroad. Rabaul was not overseas as far as officialdom was concerned. But neither was it truly part of Australia. The missing men seem to belong nowhere.

For nearly 50 years one woman worried that her husband been among those soldiers who had surrendered and was killed in grisly fashion in what’s known as the Tol massacre. In 1992, by now widowed twice, she had a vivid dream, as described to Margaret Reeson:

“I dreamt I saw a ship sink. It was going down like that. I can still see it. All this white froth and I saw a chap shoot up out of the water in a ragged uniform, and I woke up screaming out his name.”

When she had calmed down. She got up and wrote to Veterans Affairs in Canberra asking for information. They sent her a detailed reply about the sinking of the Montevideo Maru and a list of her man’s name marked. This was, she said, the first time she or the rest of his family had been told that he was on the lost ship.

There were yearly reminders of neglect around Anzac Day and Remembrance Day – let alone the July 1 anniversary of the ship sinking – with public and media commemorations devoid of mention of the ship or their loved ones. They watched and read the extensive publicity around the eventual discovery of the HMAS Sydney or the yearly reminders about the losses in the bombing of Darwin.

In 1995 for the 50th anniversary of the end of WW2, there was mass media coverage under the banner of “Australia Remembers”. But our Australian institutions and media mostly did not remember. Not the Montevideo Maru at least.

(Reeson) In at least two ABC TV presentations, it was stated that the tragic loss of HMAS Sydney was the greatest single loss of the war. In ‘A Great Survivor’ for example, it was claimed that

‘HMAS Sydney was sunk by the German Raider Kormoran and all 645 crew died the greatest single loss of life on any day in Australian history.’

In this void, a group of us formed the Montevideo Maru Society which became the Montevideo Maru Memorial Committee. The mission was to further recognition of the tragedy, the lost men and their families. Kim Beazley was our first patron. When he was posted to Washington, the new patron was Peter Garrett of Midnight Oil fame, then a government minister. Garrett’s grandfather Tom Vernon Garrett was lost on the Montevideo Maru and one of Peter’s songs paid homage to him.

We raised $400,000 for a fine memorial in the grounds of the AWM and there was a special parliamentary acknowledgment in 2012. But without doubt it was the discovery of the ship, a few days before Anzac Day this year, which finally seemed to capture public imagination.

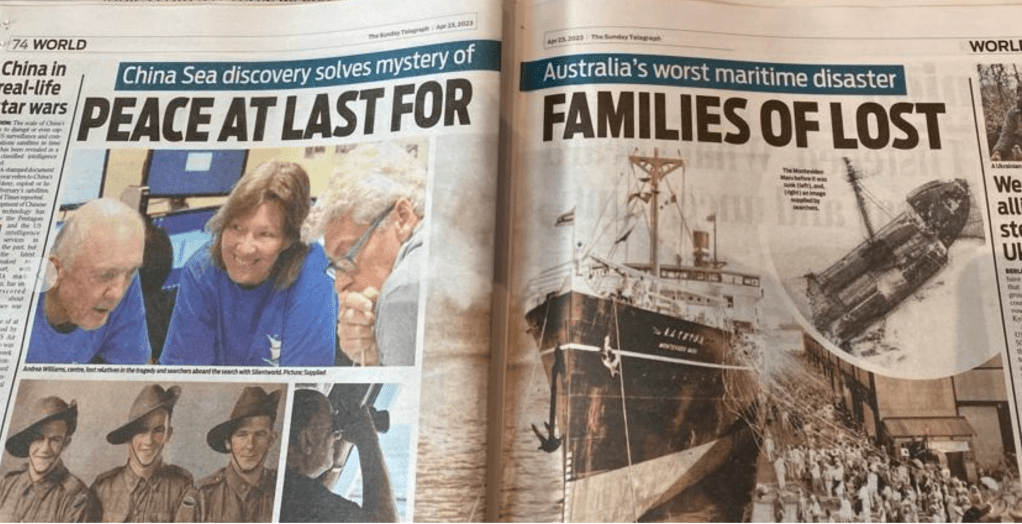

The expedition was years in the making and the driver was John Mullen, founder and chair of Silentworld Foundation which also located the missing WW1 submarine AE1 in PNG in an historic mission in 2017. Captain Roger Turner (RN rtd.) and Commodore Tim Brown (RAN retd.) were the brains trust to finding the ‘needle in a haystack’ shipwreck more than four kilometres down. I was privileged to be part of the five-year expedition planning and the search itself on the state-of-the-art vessel Fugro Equator, along with my friend Andrea Williams, who lost her grandfather and great uncle in the tragedy. Another friend and cinematographer Neale Maude took all the video images which were used around Australia and the world.

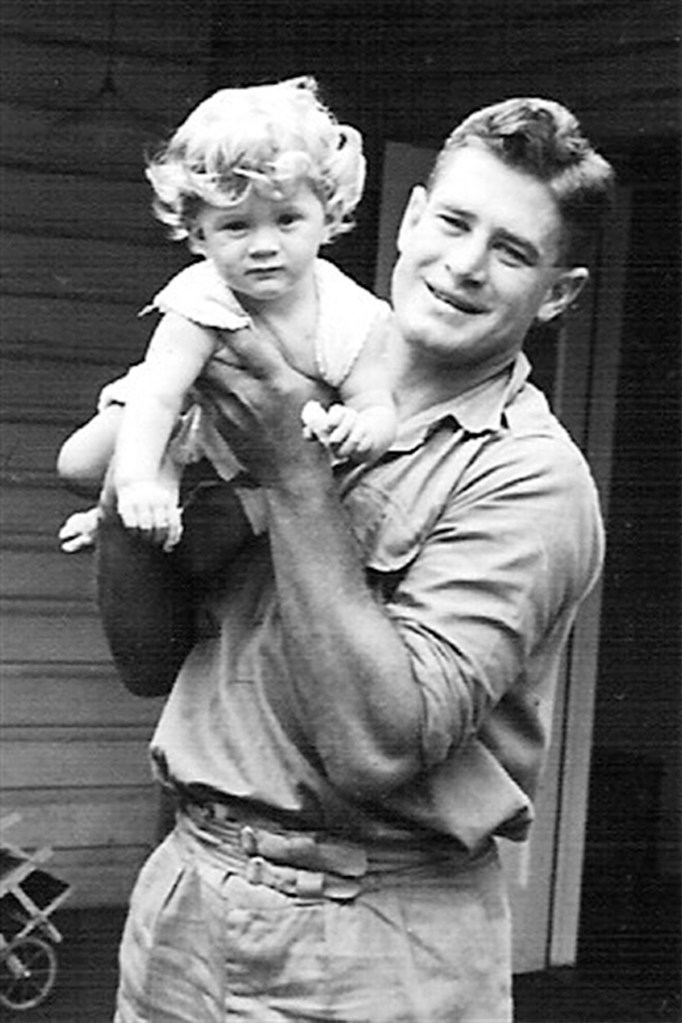

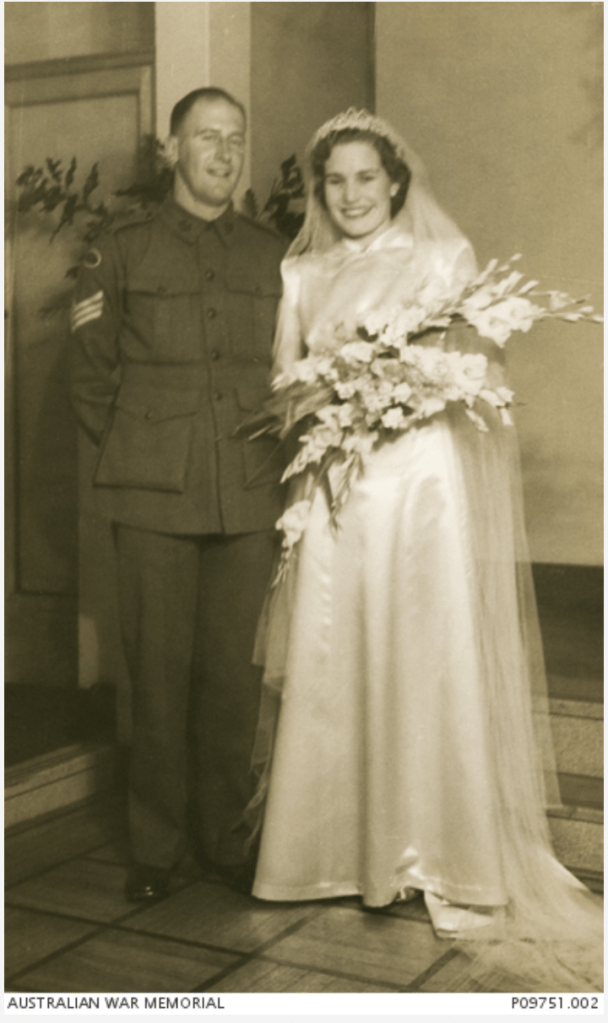

We’ve since interviewed various descendants, including Mark Dale the great nephew of the three Turner brothers – left to right below Dudley, Daryl, Sidney – who all died together on that fateful night. Mark will be at Monday’s dinner.

Mark told us harrowing stories of how the triple loss had affected each member of what had been a very happy, lively and loving family.

“They were a very, very, very close family. Unbelievably close tight family and the damage from done from that was monumental. The family was never the same. They were the only Turner males. Our family’s Turner name died with them.”

In 2008 we ran an online petition for government funding to find the Montevideo Maru and there were hundreds of emotional responses from both relatives and genuinely shocked members of the public, many who’d never heard of the ship.

None was more heartrending than this:

So, it was incredibly heartening a couple of years ago when the Defence department agreed to provide significant funding for the Silentworld expedition as well as the technical expertise of the Army’s Unrecovered War Casualties Unit.

Silentworld was also lucky to tap into the vast knowledge of a highly skilled Japanese professional who prefers to stay out of the limelight but was critical to our success.

“Closure” means different things to different people, but Monday’s commemoration hosted by John Mullen will be an important and much-appreciated emotional salve and salute to the victims and their families.

The presence of Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, various defence chiefs and departmental heads and seven ambassadors says to the descendants that Australia – and ‘officialdom’ – does now care.

ENDS

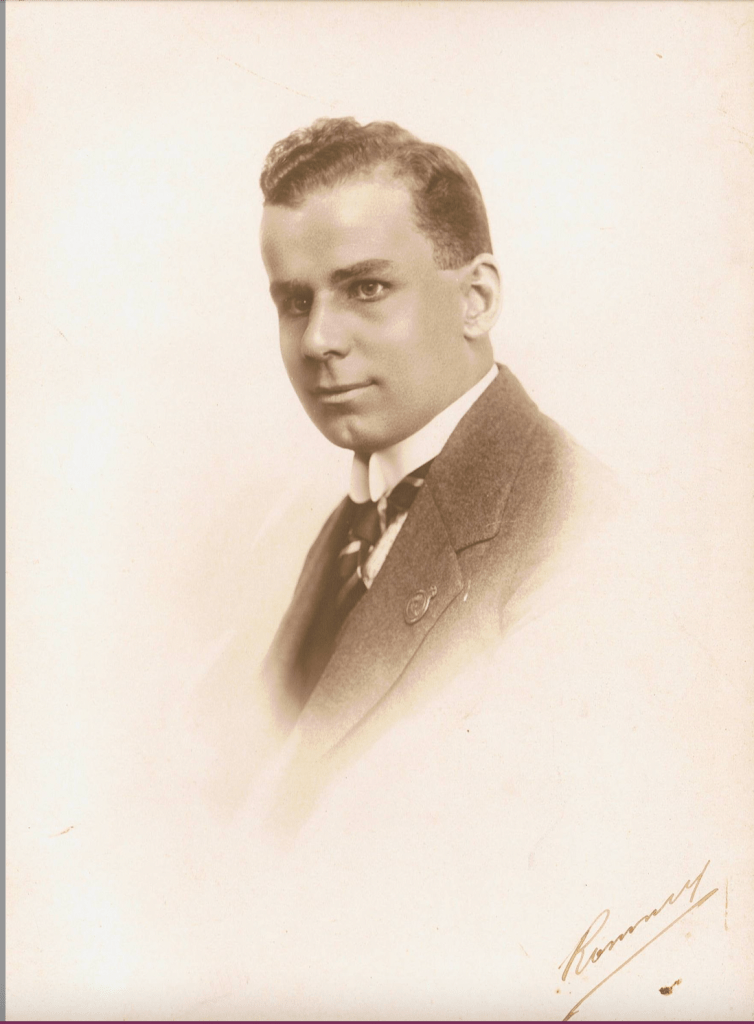

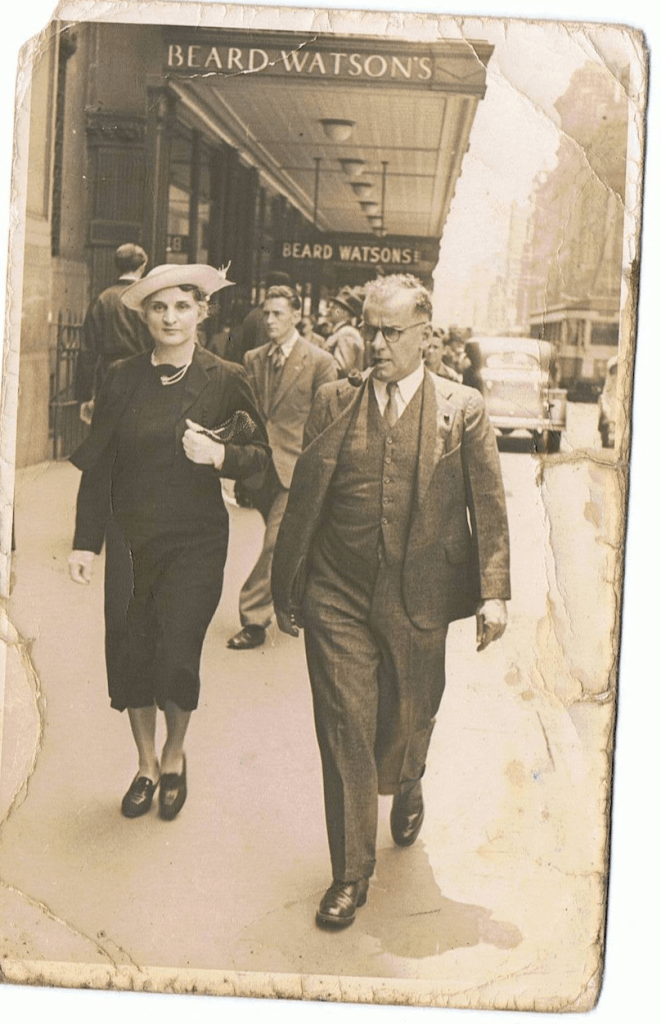

*Footnote My father Alf Uechtritz had not long turned 15 when he was evacuated from Rabaul on the Macdhui, the same ship that little Ivor Gascoigne was meant to be on. Had Dad been eight months older he would have been required to stay. If he had, he would have been killed in the Japanese invasion or died on the Montevideo Maru, like Ivor. I wouldn’t exist, nor would my nine siblings and his 33 grandchildren and dozens of great-grandchildren.Dad’s family lost a number of friends on the ship, none closer than Arthur Parry, the medical orderly who had helped at the birth of my father at Kokopo, near Rabaul, in 1926. Not all the women on New Britain and New Ireland managed to escape on the Macdhui and other evacuation ships. Dad’s beloved grandmother Phebe Parkinson was interned by the Japanese and died of starvation in captivity. Two other of his female cousins also died in prison camps. It is little wonder, then, that he spent much of his life researching the Montevideo Maru and other WW2-related events on the islands he loved. I will be thinking of him on Monday night.